"God will judge me" for indie sleaze: The Hellp seek salvation with 'Riviera'

Noah Dillon and Chandler Lucy's music spawned a culture they despise. The L.A. duo's new album is their attempt to reshape their band's "perverted" identity.

The Hellp are everywhere and nowhere at once. They claim to have spawned "indie sleaze" but are deeply ashamed of the Pandora's box that it opened. They're signed to Atlantic Records but aren't popular enough for the label to give a fuck about them. Singer-songwriter Noah Dillon shot Rosalia's new album art, directed 2hollis's "flash" video, and cameos on fakemink's album cover, and the other day, he and his Hellp co-conspirator, producer Chandler Lucy, were seen mugging on the GQ Men of the Year red carpet. Nevertheless, clout can't buy condos, and Dillon and Lucy, who both came from working class backgrounds prior to their integration in the L.A. underworld, say that they're still hurting for money.

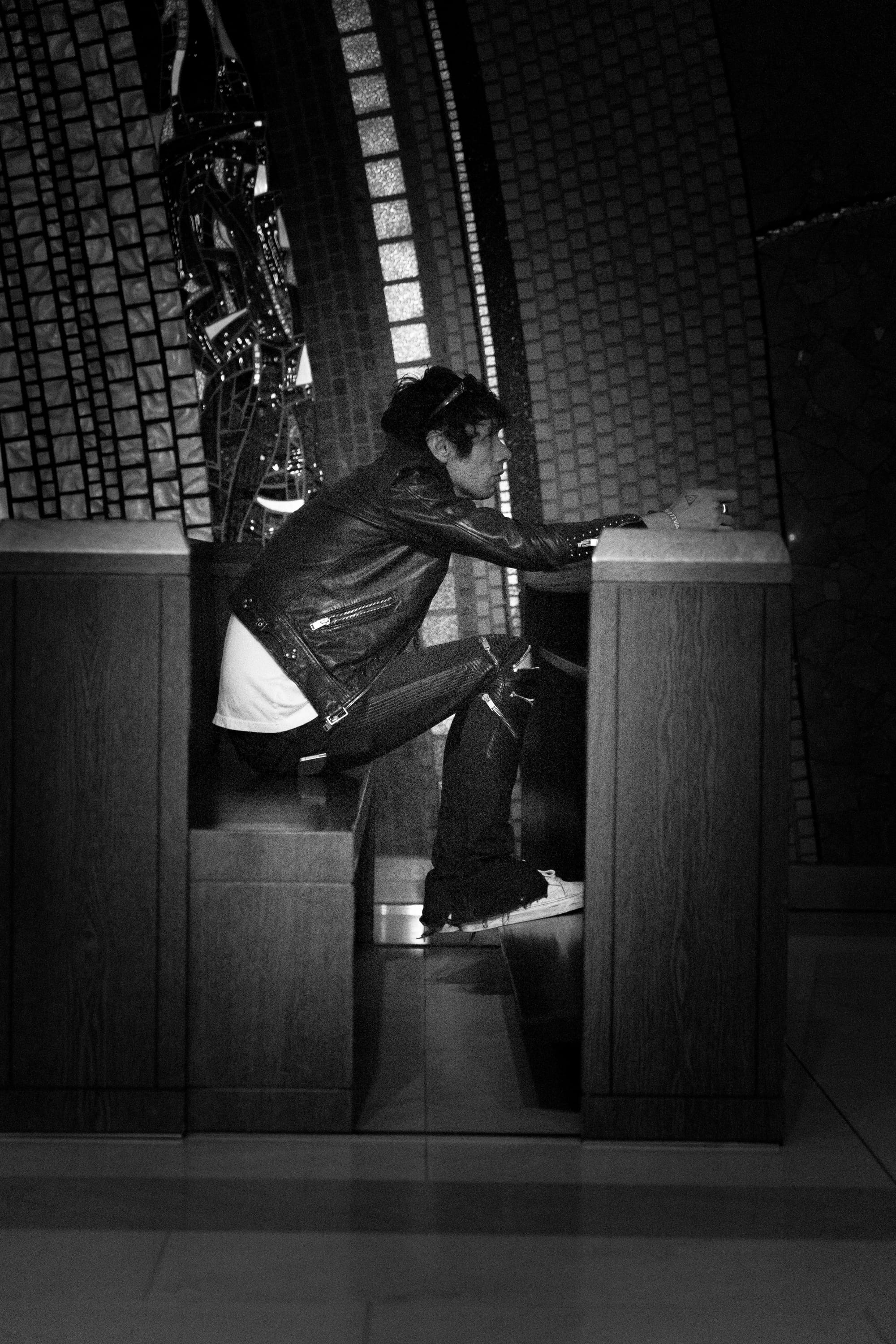

Moreover, the modicum of fame that they've achieved thus far – a sold-out North American tour, a true cult fanbase, and TikTok notoriety – is deeply unsatisfying compared to what they really desire: artistic credibility. Throughout their 10-year career, The Hellp have struggled to be taken seriously. They fully realize that their cartoonishly consistent look – a uniform of leather jackets, skinny jeans, and dirty mops of hair that resemble caricatures of The Strokes guesting on an episode of What's New, Scooby Doo? – hasn't done them any favors, but also stress that the self-expression is genuine. They're the first to admit that their sprawling discography, ranging from post-punk to electroclash to pop-punk to trip-hop, includes more duds than bangers. Dillon concedes that their 2016 debut, Twin Sinner, straight-up "wasn't good," and the two spend more time complaining about their 2024 Atlantic breakout, LL, than they do heralding it.

Riviera is their attempt to rectify. The Hellp want to distance themselves from the "indie sleaze" scene that they utterly despise – and swear "never existed" in any real artistic sense – and prove that they're not just trendy miscreants who merely want to bask in the fumes of late-aughts hedonism. Dillon and Lucy, two early 30-somethings (or "chopped 40-year-olds," according to Gen-Z TikTokers) who put Yeezus, Nebraska, and Enema of the State in the same pantheon of perfection, consider themselves real songwriters and bold conceptualists. They'd rather be critical darlings than capitalize off of the nostalgic fad that their early singles helped instigate, and Riviera is their endeavor to prove their worth and make a more highbrow impact on the culture. It's their best record, and it might be their last.

If Riviera really is The Hellp's swan song, then they'll be going out on top. The 10-track opus is as stylistically sweeping as they've ever been, sometimes recalling the clatter of Autolux or the ping of Phoenix, and at other points sounding like zhuzhed-up versions of Justice or Massive Attack. At the same time, The Hellp have never sounded as focused as they do on "Country Road," as spacious as they do on "Here I Am," or as joyfully circuit-bending as they do on "Meridian." I don't know if it's quite the classic that I predicted, and I'm not sure if Hellp fans who found them in playlists with Snow Strippers will understand it. But I place Riviera in the same category as Bassvictim's new LP Forever: "indie sleaze" denizens trying to shake the baggage of what made them famous by embracing their most tastefully outlandish artistic instincts.

Just 30 minutes after The Hellp submitted the final version of Riviera to Atlantic, Dillon and Lucy hopped on a video call to speak with me about their work, their lives, their misgivings, and their "greatness" for nearly two hours. Lucy was seated behind the wheel of his truck in Rancho Cucamonga, taking long pulls from his vape during his bandmate's breathless monologues. Dillon was in his bedroom in L.A., angling the camera up at his blank white walls so I could never actually see his face. The following conversation has only been lightly condensed for clarity. The Hellp had a lot to say, and they didn't hold back.

What does a day in the life look like for you guys these days when you’re not in the studio?

Noah Dillon: Just depends. We were playing a bunch of shows and kind of traveling around maniacally, but it’s just different between the both of us. I do the music thing and then during tour I would fly back and do a Rosalia video and shoot her covers. Flying here, flying there, and then coming back to the shows.

I walk a lot. I love to go to grocery stores. I went to the ribbon cutting today at Sprouts, they just opened one like a mile away from me, and I got to see the ribbon cutting which was cool. It was really bustling honestly, it felt like a community. There were a lot of people and they went inside and were giving away free samples and trying to get you signed up for the rewards program. It felt like good ‘ole 90s America or something.

Chandler Lucy: You went to the fucking ribbon cutting of the Sprouts? [laughing]

Dillon: Yeah [laughing]

Lucy: That's so fucking funny.

Did you hear about it or you just happened to be there?

Dillon: Like I said, I walk a lot – like a lot a lot – and I’m just a huge grocery store connoisseur. I really am obsessed with them, and I’ve been seeing it under development for the last nine or 10 months. I got the info online and the CFO of Sprouts was there for the ribbon cutting. I was like, “man, maybe I could just transfer careers right now.” There’s gotta be a world where I can just work for the grocery industry, like Kroger or something, and take down Walmart.

Lucy: But a day in the life? It really just kind of depends where we’re at and what we’re doing. The last week, until I ended up having to move into a motor home in Rancho Cucamonga, I hadn’t played Xbox in like eight months so I just wanted to catch up on all these fucking video games. So my day was usually just sleeping in, waking up, getting a breakfast burrito, playing Xbox until my thumbs hurt, going to the sauna, and then coming back home and playing more Xbox.

If we weren’t pressured on doing an album, it’s fun to make some music, go to the sauna, and go and call one of my friends and talk for like an hour, because none of my real, true friends live in Los Angeles. They all live in my hometown. I’m a lot more simple in my stimulation than most people, man. I’m just a bro from Northern California and I just like to play video games, get drunk with my friends sometimes, and listen to music in my truck. I don’t have a thing that makes me exceptionally happy.

Dillon: I guess I’m also interested in reading all the time, learning stuff. I’m, for better or worse, the Doomscroll genre of person who’s just super into Catherine Lieu stuff and philosophy. That's always been what I’ve been interested in, it just feels a little more in-vogue now, which makes me feel weird talking about it out loud.

You’ve got to get on the Doomscroll podcast.

Dillon: I followed him but he didn’t follow me back, so I gotta get my clout up somehow so he can notice me.

I looked at your Reddit and saw someone had posted a snippet of an ama where someone asked, “do you feel like you’ve made it?” and you, Noah, said “no.” Why is that and what would "making it" entail to you?

Dillon: I said “no” because I’m always an unhappy person who’s trying to reach into the future to make myself happy now. So psychologically, that's probably the primary motive for saying that. But truly, it’s because when I started all of this, I was from Colorado, didn’t really know anything, there was no artistic idea or output, but for some reason I just had this burning desire to do something impactful. And the people that I started researching, the premier artists of their time and of their sub-sect and of their genre…those people who are my heroes, whether they're philosophical thinkers, whether it’s Jesus Christ, Lou Reed, Mike Kelley, those people are what I’m striving for, and I haven’t really done anything [like that].

I’ve done very, very few things, maybe one or two things, and I’ve created this little cultural economy that The Hellp is, that have touched on greatness. And that's what I’m here for. I saw that Reddit thread and I saw the comments, “Bro, he just can’t be happy with anything.” And I’m like, “you wouldn’t understand,” and I can’t really say this out loud because of course I sound like all the things that people may or may not think about us, but their idea of success is, “Oh, they sold out a North American tour.” Bitch, I don’t give a fuck about that. I don’t care – at all.

Yeah, it’s really hard to do that and I’m proud of us for being able to do that. And that was a dream of mine, to have a room of, well, now the rooms are much bigger than this, but my dream was a 200-person room where everybody is vexed by us onstage and it’s really transformative to culture. And we got that, so that's great to check that off, but that has nothing to do with really penetrating the zeitgeist in an artistically integral way, and that's what I’m here to do. So of course I’m not fucking happy. My life sucks half the time.

Yeah, I don’t want to complain, but it’s depressing and we don’t really have any money still, somehow, to this day. The operation behind the scenes is completely flummoxed and on the border of breaking down even though we ostensibly have this built-out team. These are all obstacles that we have to overcome. I’m definitely not happy yet, and I probably will die unhappy to a degree, that's just the nature of it. But I want to achieve greatness and it’s really hard to do that, and these other social markers that others may be happy with, that they think that we should be happy with, or I should be happy with, don’t really affect me. Because my metrics and my grading scale is based on a different criteria from what a lot of people see on the outside.

I'm trying to make some very good shit, and it’s really hard to do that and I’ve barely done it, and it’s alchemic and magical if you’re able to do it. The Hellp, unfortunately, the idea of it has been perverted. Partially because of our antics, which aren’t necessarily antics, it truly is who we are. Like, oh we’re insufferable this or that, and if that scene is insufferable, whatever. We’re cool guys, when it comes down it, we’re just normal fucking guys more or less. But the idea of The Hellp has been redefined and perverted by this, and I really hate to say it, but this younger Gen-Z crowd who are judging people off of different criteria and different merit. Whereas the schtick, I guess, however we act, was much more accepted and hailed around 2017-2019, when it was a bit older people and it was these sort of pretentious art-school types and faux-intellectuals, or even intellectuals.

It was more of that and less, “Oh, Noah and Chandler are chopped 40-year-olds,” or whatever. The crowd has changed and the context has changed and it’s sort of been ripped around and we haven’t been able to do much about it. It used to be very, “oh, the music videos, these are borderline fine art,” and they're really important to the ethos and the mythos of the band. But people don’t give a fuck now. The “Go Somewhere" video I thought was a good video, and literally no one cares. You’re never gonna see it on TikTok and the view count is really low.

It seems like you’ve ended up at a place where you didn’t want to sit culturally. Where did you want to end up?

Dillon: I wanted to end up on more like Yves Tumor, Smerz, Dean Blunt, or even, worst case scenario, Geese. That was how I wanted to be seen and perceived, but there’s two beasts inside of me. One of those beasts wants to be that, but the other beast was like, “No, I’m really insecure so I want people to be screaming my name,” and to do that, you have to sacrifice some of the artistic merit. And you make a song like --

“Ssx?”

Dillon: No, I think “Ssx” is brilliant, to be honest. I’m talking more about like “Caustic” or some of those songs that are clearly not good songs, but they are good at the same time depending on the parallax view you want to look at them in. You can’t ever get exactly what you want, so you just kind of ride the wave and see what happens. But I’m a control freak and I’m like, “Ah, fuck, people think this and we’re not doing that.”

It’s just annoying that some of our good work like the Enemy EP, which I think is borderline brilliant, and some of the other tracks – people never talk about them. People form their opinion off of seeing a TikTok of me explaining why I’m on the fakemink cover and why they hate it. They probably heard “Caustic” for 10 seconds or “Tu Tu Neurotic” – and I would hate those guys too.

Lucy: I saw the same Reddit post and I basically felt the same way but in a much more simple way where I was just immediately was like, “you guys just don’t get it,” and it’s fine. And you can talk all the shit you want saying Noah’s not happy, but we still haven’t played fucking Coachella. We’ve barely been talked to by any real publications and haven’t been taken seriously. So many other people that are so much less artistically credible than us have been, so it’s just hella frustrating.

But I was thinking about our fanbase or perception getting hijacked, I think a lot of that a lot of these young fans, these Gen-Z 18 or 16-year-olds, they never really quite had a voice in being fans of shit. But now all these young kids have the ability to talk hella shit on the internet and steer things in a direction that they want to, which can be very terrible but also pretty beautiful, I guess.

Dillon: Well, yeah, it’s been told that everyone’s opinion matters now to an umpth degree, and combined with that, people want to be the center of their own spectacle. It’s not like it’s that much different [than it once was], it’s just that your opinion online actually has real-world ramifications post-cancel culture. I remember YouTube in 2013, the comment section was very integral and important, but it was still more anonymous. Whereas now everything’s attached to your identity and name and you can become a person of simple and quick power and have drastic, tangible, real-life consequences from your opinion.

I’m curious why you guys would want to play Coachella. Like, that's a marker for achieving success while maintaining your artistic credibility in 2025? To me, Coachella has just become so watered down, and with these gatekeeping institutions from the 2010s and the 2000s, there was once a real esteem to being on Coachella or Pitchfork. And now, a lot of these gatekeeping institutions that these Gen-Z kids rail against, because they didn’t grow up in a culture of gatekeeping, just don’t have the value that they once did. But they still seem to matter a lot to you guys.

Dillon: It’s just cause we’re old-heads. It meant a lot to us back then. Like, I really wanted to play late-night television a couple years ago, and obviously no one gives a fuck about that anymore. But I just had this vision that three years ago, if we played late night – and this was before the hoopla of indie sleaze really took hold – and played a song, people would get it and it would change things for the better, but we didn’t. So yeah, it’s just stroking the ego of the inner child, because we’re just from more of that time. As opposed to 2hollis playing Coachella this last year, and he didn’t really give a fuck. He’s like, “yeah it’s cool,” but it’s just kind of another festival to him. And a lot of these kids don’t really care either.

There’s a quote from The Face interview where you said, Noah, that your goal with The Hellp was to move the underground in some capacity, and you felt you did that by 2019. Why do you feel like you achieved that by that point?

Dillon: It’s one of those things where nobody knew who we were really. There was a tremor that happened, but you didn’t know what it was from. Twin Sinner, the first project, wasn’t good, but it had a lot of heart and soul in it, and that's what a lot of people identify with. There’re still fans like, “That was the best project,” because you can hear my passion. But the music was bad. That's OK because you’re learning, and one video came out of it that I still think is almost an unparalleled work, but I changed the band, too. I wanted to do more electronic music. The day that Twin Sinner released I started making that and brought Chandler in shortly after.

Chandler and I come from a fashion community, like that's really what kind of brought us together, on this shoot I was photographing and he was a model for it. That's how we met. But we’re from this fashion community and no one looked like us or was dressing like us. It was very polarizing to people. And I don’t know if this is something I’m gonna get posterized for in a bad way for saying, but that was the height of Soundcloud rap culture, and there wasn’t really any indie/electronic white boy swag, whatever the fuck you want to call it. That was such a mid-000s era derision, and people who were interested in that, or didn’t even know they were interested in that, grabbed hold of us and were ride or die. They were obsessed. There was few of them, but it was a very ride or die thing.

Now, that sort of thing is very in-vogue. Geese, The Dare, Drain Gang. I’m not necessarily saying it’s like a race thing, it was just a cultural thing. The pendulum was swinging a multitude of ways, but I was trying to bring it into the references in my wheelhouse. Which was, Oh, I really like the Crystal Castles stuff, I’m really obsessed with Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, and I’m from Colorado and everybody hates me here, and all the cowboys hate me, but it’s all interesting. We made some songs and some people liked them and it became a bit of a cult following. And by 2018 “Ssx” was made, and then “Tu Tu Neurotic” was put out in 2018, and the first nine months it didn’t do anything, but after that it suddenly became this little phenomenon in New York, in the lower part of Manhattan. Where, if you were cool, it was your favorite song, and girls were getting tattoos of it. It was the “if you know, you know” thing.

That was the start, and I’m not saying that song did all the work, but it was a catalyst and a large component of the predecessor of, for better or worse, Dimes Square. I was in Manhattan at that time and there wasn’t that scene. It was a clout scene. It was like, “Oh, we’re gonna to some restaurant where bankers go, and we’re gonna go to this club that was like a bankers club.” There wasn’t an alt-lit scene that was burgeoning, it was different. So that song really helped kick all that off. By 2020, we played our first show in New York and it was kind of a renaissance and the ushering in of a new scene. And a lot of people who are making music now, who are popular or are credited as part of this thing, they were in the crowd. There’s videos of them there [at our show] and they're just kind of looking with wide eyes. It was because they realized, “Oh, now is a time we can do something like this.”

I’m sorry I’m taking credit for it, it’s just that we inspired people. And they’ve all said privately, “Oh, we really fucked with what you’re doing, you’re a really big inspiration,” that sort of thing. I don’t think there’s any reason to sway away from it. If Chandler and I were really popular, there would be no need to say any of this shit. But we’re still having to fight every second for people to think that we’re valid in any sort of way, so it’s really hard not to bring up, “you didn’t know what the fuck is up, we really had a hand in all of this.” I’m proud of that to a degree, even though I think that this band may have fucked things up in a bad way.

There are some acts that were inspired by us that I do enjoy, but the broader sense of culture that we have inspired and had a large hand in creating, I despise. And I think God will honestly judge me hard on that. Like, my dad thinks I’m gonna go to hell for some of the creative works I’ve done. I think I’m gonna go to hell because of the outcome of some of the creative works. Not because of the advent of that thought, but because of how people interpreted them.

Lucy: Like Noah said, we came from this fashion world or whatever. I think we developed this muscle early on to sense these tremors of shit changing, and this may sound braggadocios and we’re not necessarily proud of this at all, but nobody was wearing Rick Owens until Noah and I started wearing Rick Owens. And then our clouted friends started buying Rick Owens. Nobody cared about cowboy boots, and then Virgil Abloh saw it and hit up Noah saying, “I’m gonna make cowboy boots just for you.” And then it was the trucker hat thing. Nobody was wearing Chrome Hearts trucker hats and then our associates who have those platforms started copying us directly. So we started to sense these moments like, “oh, cowboy boots are coming back. Ah fuck, now everyone’s wearing Rick Owens again.”

I’m not saying we’re singlehandedly the reason Rick Owens had a huge resurgence the last five years, but we definitely were like this spark that made everything happen. So when this shit started happening in 2018 with our music, we were able to witness this tremor and see one thing happen and go, “yeah, that's about to happen.” We kind of just always had this muscle of being like, “oh shit, we’re not getting credit again.”

Dillon: Maybe we don’t need credit, but Chandler’s right. That's what I’m pretty good at, is just sensing what’s going to be next. I’d be a better Sean Monahan or critic or trend forecaster than I would be an artist.

So is Riviera guessing what’s coming next and setting yourself up to be there again? It feels like a very decisive pivot in a lot of ways from the last record.

Dillon: This is the first record where I consciously made the choice not to try and be ahead. Every other record except for Twin Sinner, which was me actively trying to participate in a scene that I couldn’t physically be a part of, which was Burger Records, Teen Suicide, that sort of scene.

Oh wow, interesting.

Dillon: Yeah, I’ve never really talked about that, but the thing that was happening then was the Burger Records scene and like Sunflower Bean and I was honestly really inspired by that and wanted to be a part of it.

Teen Suicide was adjacent to Alex G then. Was that your bread and butter as well?

Dillon: Of course. One of my favorite songs of all time is this unreleased – well, he released it – but it’s called “Track 09.” But yeah, huge inspiration. I’ve never actually talked about Alex G. He’s a genius, honestly, and he has not gotten enough credit.

But yeah, so that first record [Twin Sinner] was not trying to be ahead, that was trying to participate in. All the other records were trying to be ahead. This record, Riviera, is trying to be us as much as we can be right now. Maybe people don’t like it or maybe they will, but I really wanted to make “real music.” I wanted to be more restrained. I wanted it to be better songwriting, which, I should’ve spent more time writing lyrics on it but there just wasn’t enough time. We needed probably two years to make it, not nine months. There was emphasis on a more traditional sonic and songwriting approach.

LL wasn’t even an album, it was more of a mixtape. Chandler describes it well where he talks about how it feels like you’re switching channels on the radio station, but every channel you switch it to is like, “Oh, this is pretty cool.” It’s pretty cool, but it’s not cohesive. LL was trying to be ahead, but it was also trying to show everyone else around us who was inspired by us, “Hey, fuck you guys, we can can make banging music just as good as you, if not better.” Whereas this record is not that. It’s trying to make good music for the age that we are now. We’re too old to be trying to compete with guys who are 21 years old who can make five different genres and for some reason it works because youth smooths over a lot of the inconsistencies.

It doesn’t sound comparable to Snow Strippers or Bassvictim or some of these other acts. Some of which I like, some of which I really don't.

Dillon: I really like the new Bassvictim album. I was really surprised – that sounds negative. It just, it’s really hard once you have this cultural, phenomenal record, which was Basspunk one. Like, after you do that, it’s really hard to come back from that and do something that's better. And they were able to do that with this latest record, I think, so that was cool to see.

It’s a total reinvention. But how do you feel like these Riviera songs are better than LL? What aspects of them feel more legit in that regard?

Dillon: It comes down to a lot of things. One is just the palette and the paint that we’re using. I was trying to use more tasteful components for the palette. Instead of, you know, “Caustic,” where the vocal sample – “aye-aye, aye-ya-ya” – that's clearly a very cheesy, pop, whatever. So leaning away from things like that. Some of the references, even though you necessarily can’t hear them, used to be a bit more tasteless but commercially successful. Whereas this record the references were Portishead, Massive Attack, Bruce Springsteen’s Nebraska, late Velvet Underground, Metal Machine Music. That kind of stuff was constantly in my brain. Like “Country Road,” I was trying to make a Massive Attack song.

I’ve never really been a huge fan of my lyrics. There’s been some stuff that's kind of cool, but it’s never been the forefront of what’s going on here. So trying to write a bit more cogent, a little bit more storytelling, a little bit more cohesion and less magical realism and metaphors. Another big component is that, historically, demos that we have are reworked countless times. Like, you make the thing and it’s reworked and reworked and reworked until it’s a completely different song, because I’ve always been so, “this isn’t good enough.” And that didn’t happen with this record.

I saw a comment online where some guy was like, “Bro, Noah needs to quit the band, he’s a cancer to this band. It should just be Chandler producing.” And he’s completely wrong for obvious reasons, but he’s also not totally wrong. The only reason demos have been worked to oblivion is because I’m insane and want it to be that way. But this record, no songs sound drastically different from their inception. “Country Road” is exactly how I made it the first time I made it. “Doppler,” that Chandler spearheaded, sounds identical, more or less, to how it was first made.

Lucy: Only a handful of these songs are pretty old but I think we kind of achieved this freedom now where we’re not 24 years old anymore, and that freedom has allowed us to be much more reductive in our music. I think what’s the most important thing at this stage in our “career” – it’s weird saying "career," but I guess we’ve been doing this for almost a decade – is making sure that it’s unequivocally just us in every way. Not that we historically worked with tons of people, but we had a few songs that have been bounced around by too many people that kind of lost their identity. There’s some stuff on LL that probably should’ve been incubated in our chamber pot for longer.

With this one, we assembled a “team” and they helped guide a lot of things, but when it comes to production and writing, that was 99% us. To me personally, that's the most important thing with what we’re trying to achieve. Like you said with Twin Sinner, it’s not necessarily the best fucking songs, but you can feel that it was a fucking kid in Colorado who wanted to prove something and genuinely believed in it. I don’t think necessarily that this album has that same spirit, but it’s definitely capturing a moment in time of what we wanted to achieve this last year. Or even what we wanted to achieve in 2018 with a song like “Doppler” or “Live Forever,” which we initially made in 2018 or 2019.

Riviera definitely feels less overwrought. Sometimes that was what made your guys’ music fun, and there’s still so many ideas happening in some of these tracks, so many shifts. But songs like “Here I Am” and “Country Road” especially just feel very smooth, natural, and spacious. It was refreshing to hear you guys in that mode.

Dillon: Funny you say that because “Country Road” I made in one sitting, basically, and “Here I Am” was the same way. “Here I Am” is the only song on the record where I’m like, “I want to make a hit.” It’s funny how the bed I’m sitting in now, this is where 99% of my music is made, and you’re just sitting in this little apartment. I never really subscribed to the Rick Rubin narrative and all these seemingly smoked-out individuals that would say, “oh, you need to have the perfect vibe to make the music.” I’m like, “Fuck that dude, that's bullshit.” I think I was wrong.

We had this ridiculous Airbnb in Beverly Hills overlooking the city, and the sun was setting and I was sitting there in this glass dome where you could see this panoramic view of the yard and the pool. And I’m sitting there and I’m like, “I’m gonna make a hit,” and that was “Here I Am.” But I would never have made a song like that, this kind of Kavinsky “Nightcall”-esque song, I would never have attempted that if I wasn’t looking at this view of Beverly Hills. That's what’s helped The Hellp music, the circumstances in which we’ve made it. Some of it’s been in black mold apartments and during hard times, whereas this record, we finished this music in multi-million dollar homes – and it doesn’t sound like it. The feeling of the music, you would not think that these guys were sitting in the mansion [where] the week after us, famous Onlyfans girls were doing their thing.

But I think it plays into the narrative of Riviera, as the title, which is this escape. This disparate Americana, the American Riviera, the west coast, and the metaphorical idea of the Riviera. Chandler and I still think of each other as blue collar guys, because we really are. That's where we come from and it’s still how we approach this stuff. So you get a couple blue collar guys who are ordering Goop Kitchen, like Gwyneth Paltrow’s company, to this multi-million dollar mansion, making songs that are a bit more disparate, but we’re in the lap of luxury. It’s a good tension. I think that actually helped how things sound on the record.”

Lucy: What you mentioned about “Here I Am” having space to it, and these floor-to-ceiling glass [structures]. I remember our engineer saying something one time at his old studio where he was like, “you notice how I got the computer right here and I got eight feet to the wall? You need that because your depth perception gets all fucked up staring at the computer too long.” And I was like, “yeah whatever, dude.” And then I remember being in [the Airbnb] with a window right there and a pool, my girlfriend’s dog running around, she’s with her hot friends in a bikini, and it’s this big open landscape. I think that aided in the ability to create these sprawling fucking landscapes that were huge. Like, the instrumentation in “Live Forever” or the beat switch-up in “Meridian” and all that stuff.

Dillon: Usually the music was made in confidence, either alone or in a closed-off studio environment. But these houses, especially the first house, it became this performance. I’d be working on a song at 2 a.m. and there would be a party going on behind me outside. There’d be like 80 people there and I would have to be performing for them, because you don’t want to fuck up in front of other people. And I thought that that would not help the record, because I’m very temperamental and am like, “oh, you can’t hear this, it’s not ready.” But it actually made the process a lot better and I think the quality increased because of it. Theoretically, if there’s five attractive women behind you, you’re gonna want to make a cool sound. As opposed to if it’s just you alone and you’re like, “oh, I hate myself, what if I ordered a snack?”

Lucy: A bunch of people were coming in and out and we have these $12,000 speakers and 30 synthesizers and drum machines in front of us. So when you’re in front of these people with this giant studio, you have to impress the speakers, and when my girlfriend and her friends, or anyone on our team is coming through and hearing us work on a fucking beat, it better sound awesome. Or then they're not gonna think that we’ve made it.

I’m curious to know about the intention behind the “From LA to LA, la la la” part in “Here I Am.” Because it feels like such a jarring changeup in the middle of this really taut, beautiful, plush song, to suddenly have this snotty vocal singing this easy chorus over it. I don’t even dislike the part, I’m just confused by it every time I hear it.

Dillon: I’ll probably never say this again because maybe it’ll ruin a few people’s perception of the song, but I wrote the song about the movie Heat. These ephemeral characters in this sprawling Los Angeles landscape, stealing money but you don’t know what’s going to happen. Holding hands but you don’t know if it’s a love story or if something terrible is happening, that sort of thing. And when I was making it, Maggie [Cnossen], who isn’t even really my assistant, I don’t know what Maggie is. She’s my day one. She’s assisted me on almost anything I can get her to be on and she also does the graphic design and implements my ideas for the packaging and logos and different things like that. She also tour managed us, and is very integral into my process.

She’s sitting next to me and I wanted to use Maggie to help with songwriting, and I’ve never had anyone help me with songwriting before, ever. And I thought, “well, Maggie’s cool, she knows some of the same stuff I do, so let’s see how it works out.” And she’s quite an insecure person and I’m making the beat and I’m getting excited like, “this is cool.” Then all the sudden under her breath she said, “From LA to New York,” and I paused and was like, “What the fuck did you just say? You're recording that right now.” And then when she actually did it, she said “LA to LA” accidentally, but then I just kept it, and then we kept doing “LA to LA.” It’s just so stupid, the stupidest fucking thing you could ever imagine. This sudden imposition that changes your idea of what maybe the narrative, or even what the landscape, even is.

It became a caricature of The Hellp in that moment.

Dillon: Exactly. And that's really how I work no matter what the medium is. I thrive on accidents and these little things that happen that are unexplainable, I always accumulate and put into the workflow. A lot of people are too afraid to integrate accidents because it doesn’t logically make sense, whereas I love to embrace it, and that's why a lot of our music sounds the way it does. Something really fucked up happens and we just integrate it. So, Maggie was a total accident. I didn’t even know Maggie could sing. I had no idea she could do that. She’s never written something, she’s not that girl. It was the most fun I had making any song on the record. Everything else was hard and I started to hate it, but “Here I Am” was a lot of fun to do.

She sings on “Country Road” too, right?

Dillon: Yeah, she does. I had this flow in my head from a Danity Kane song, “Do, do, do you got a heartbreaker baby? Are you patient, understanding?” I was like, “that would be really cool,” if we went whatever [Maggie] says, “do, do, do you connect all the dots?” For some reason a girl vocal in that key and tone feels so fresh. It’s the perfect contrast to have in that song because you’re used to this male voice, and all of a sudden you have this sharper frequency that kind of re-contextualizes the song a bit before it explodes into the ending.

You guys are still on Atlantic Records. Do you get any pressure from the label, or feel pressure from any direction, to compromise?

Dillon: To be frank, the label doesn’t give a fuck about us, really. We’re not making them enough money for them to really have an opinion. They kind of just like the idea that maybe once a year people think they're cool because some people think we’re cool. I will say, there are some people on our “team,” close-ish to us but not really, who love to give their little opinion. Because secretly they want to be artists, and they're not. And so this is about as close as they can get, so they want to tell Chandler and I what to do. But we’re brash characters and say “fuck you.” We say “fuck you” on one hand, but in the back of heads we’re like, “maybe we should change it…”

Lucy: At least on this record, we really only felt pressure from ourselves. Anytime anybody did say anything we would be like, “Yeah, how about you shut the fuck up. Because it’s our song.”

Dillon: We wanted to make a tasteful record so we assembled this team. Tom [Krell], who is How to Dress Well, you know, a Pitchfork darling in his 40s. He knows what good music is, high taste level. Tray [Tryon], our engineer, has good taste. There’s different opinions, and Tray has an opinion, but it usually came down to what Chandler and I wanted. Like, there was a song that didn’t make the record that Tom texted me about 50 times being like, “you’re such a stupid idiot for not putting this song on the record. Why would you do this? This is the hit of the record?” And we just didn’t put it on because it would’ve ruined the continuity.

It’s like in the latest Top Gun with Tom Cruise. You’d think he’d pick the hotshot of the crew because he’s clearly the best pilot, but Tom Cruise doesn’t pick him to be in the mission because he’s too good. He needed the team to work as a team and not the New York Yankees when they decided to try and make an all-star team in the mid-000s and they lost everything. We tried to pick the best songs to make the best record.