Humor, despair, survival: A long talk with Coma Cinema's Mathew Cothran

The grand delusions of an indie-rock auteur living in exile.

Finality has haunted Mathew Lee Cothran for his whole life. For years, he'd go to sleep every night assuming he wouldn't wake up the next day. Throughout his prolific music career, he's treated every album as if it could be his last. He assumed death was imminent, that the wounds he endured as a child would never heal, that he could numb himself forever, and that every song he wrote could be his final words. And then he just kept on living.

Twenty years and 20 albums later, Cothran is still here. He's writing some of the best material of his life, including the newly-released Grand Delusion, the first Coma Cinema album in eight years. He's healthier than he's been in a long time. He's no longer fixated on the end of his life, the end of his music career, the end of his involvement in an artistic community. Now, his mind is occupied on new beginnings.

In 2005, Cothran began writing music under the name Coma Cinema. After releasing five albums through that moniker, he put the project to bed with 2017's astoundingly bleak, heart-wrenchingly beautiful Loss Memory, and then focused his energy on other musical projects: Elvis Depressedly, The Goin' Nowheres, and the albums he released under his own name, Mathew Lee Cothran. In the eight years since he disbanded the band that made him an indie-rock cult figure, Cothran's life changed dramatically. He battled mental health struggles and various addictions. He left an abusive relationship. He stopped playing live. He released a boat-load of albums. And, for reasons both voluntary and involuntarily, he severed ties with the indie-rock ecosystem he had long been a part of.

In 2019, his former tourmate, Sam Ray (Teen Suicide, Ricky Eat Acid), posted a since-deleted Twitter thread accusing Cothran of emotional abuse. Cothran responded with a since-deleted Medium post refuting Ray's claims. The two musicians have traded barbs with one another on social media in the years since, and the blowback from that situation has effectively exiled Cothran from the music milieu he was once a prominent figure in. He's released a half-dozen albums in the 2020s and most music publications have declined to cover any of them. He hasn't toured since pre-COVID. He's very open (including in the below interview) about the issues he has with his former label, Run For Cover Records, and he's always been a provocative presence on social media who's liable to call out musicians he has negative opinions on.

None of this has ended Cothran's career outright. The Coma Cinema catalog is more popular on streaming services than ever, and he has the kind of passionate, albeit niche, fanbase that most small-time artists dream of attaining. I'm one of those fans. I never stopped listening to Cothran's material and am one of the few music journalists who's continued covering his output in the 2020s. While not all of his stuff hits for me, he continues to be one of my favorite songwriters ever. I find him deeply moving, gut-bustingly funny and nearly unmatched at writing sticky, stylized songs within the "bedroom-pop" format. Grand Delusion, self-released on June 20th, is one of the best, most honest albums he's ever made.

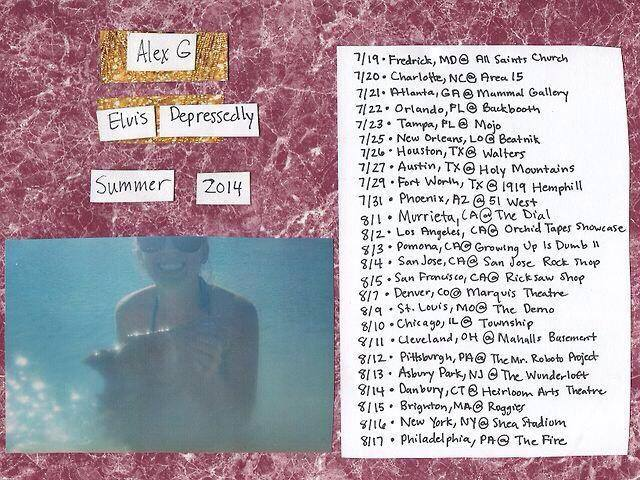

In a different timeline, Cothran would be one of the biggest songwriters of his generation. As a teenager, he was pulled under the wing of Toro Y Moi's Chaz Bundick, who mentored him and helped facilitate Coma Cinema's early – glowing – coverage on sites like Pitchfork and Hipster Runoff. He toured with Mitski, Alex G, and Turnover at various points in the 2010s, and made a record with two of the guys from TV Girl, who are now one of the biggest bands on the internet. Cothran's bands were pivotal at popularizing the style of home-recorded, self-released, cassette-appropriate music that hi-jacked the indie zeitgeist by the end of the 2010s.

He's been right there for so much indie-rock history over the last two decades, yet he's never attained the household name status that many of his peers have achieved. Beyond loving his music, I find him to be one of the most interesting figures in contemporary rock music, and with the arrival of Grand Delusion – a record about forgiveness, survival, persistence, and joy – I decided it was finally time to interview the guy after a decade of following his work from afar.

Just as I hoped, Cothran was in a chatty mood for the duration of our four-hour Zoom conversation. He generously entertained all my questions about his bizarre upbringing, walked me through his entire music career, and divulged stories about his personal life that reveal the remarkably self-aware, sincere, flawed, and well-intentioned human who's written all of these bleak, hysterical, intricately human songs.

Where are you calling from right now?

I'm in South Carolina. I moved back. I was in Asheville for like 10 years, and then [hurricane] Helene was really awful. It was already getting kind of hard to live there because of the rent. It's like the San Francisco of the South, Asheville. And it got real strange there. I would see so many people who were kind of famous walking around Asheville. I hung out with Moses Sumney one time in Asheville. And he was like, “Oh, I moved here.” And I was like, “what? Why?” And Angel Olsen…there was a lot of famous indie rock people there and I was like, “This is a bad sign, my rent’s about to go up.” And it did – drastically.

I was planning on leaving eventually, but Helene really expedited that process, and it was super rough. There was no water, you couldn't text anybody. It was a fucked up situation. I have PTSD anyway, so when I get more PTSD, sometimes it's hard to realize that it's different now. So I would be feeling horrible, real paranoid and scared, and I’d be like, “what's going on? Oh, you just went through a natural disaster” or whatever, and I'd have to kind of remember that. But things are better now. Everybody's safe that I knew. Everybody went through some hard times, people helped each other.

Besides moving back to South Carolina, has your lifestyle changed at all?

Yeah, I'm a lot healthier now. My mental health has never been great. And then I used to drink all the time – and anything and everything else. And now I'm like…what's it called when you'll drink socially but it doesn't run your life anymore? Is that California sober?

I think California sober is for people who smoke weed but don’t drink.

Oh, OK. I'll have a couple drinks here and there if I'm out in public at a gig or something. But I don't drink at home, and I haven't for a long time. I feel a lot healthier overall. Eating better and trying to live longer. But, you know, I did a lot of damage over the years. I could fall dead at any minute. I want at least to feel healthier, and I do. I feel pretty good. I lost a lot of weight. I started to look like Jim Morrison before he died for a while. Even with the long hair and stuff. But no, I'm feeling better. My perspective is better. I'm more positive, and I have more joy overall in my life. My twenties weren't very fun. I hope yours were more fun. Mine were kind of shitty.

Why were they shitty?

There were some really great parts: certain tours, some people I met, seeing the world. But I also let people kind of run my life and I sort of gave up autonomy over myself. I took going with the flow to a conclusion that wasn't very beneficial. I didn't really assert any boundaries. And I don't know, it's probably lessons that everyone learns about trusting people and taking care of yourself and taking care of your mind and your body, but it took me a long time to figure it out. There's a John Lennon song called “Life Begins at 40,” which is really funny because that's when he got clapped. But he's probably right, it probably does begin at 40. Just not for him.

But yeah, I'm looking forward to that. As I get older, my mind feels younger. I have friends who are in their twenties still and I try to tell them to love themselves and act out of love for themselves. Take care of themselves like they're a child. Because that's sort of what we do anyway. We're sort of guiding this inner child through the world and trying to protect it. Trying to give ourselves the protections we didn't have as children.

Speaking of being a child, you grew up in South Carolina, right?

Yeah, Spartanburg.

What’s the vibe there?

It’s a trippy place. When I meet people who are from there, we all have the same vibe. There's a lot of people from there who have a gallows humor. It’s kind of a rough place. And people from there have a tendency to laugh at shit that might be not funny to some. I think it's just because it's a rough town, there's not a lot to do. When I grew up it was very backwards in a sense that my road didn’t have paving on it. It was one of those old dirt roads…that kind of shit. But that was real, and it was a very Harmony Korine childhood I had. When I watched Gummo for the first time there was a scene of a bunch of guys getting drunk and wrestling some chairs. And I was like damn, I watched my family do that. I seen that shit before.

My dad was a real bad guy. He still is. He’s not in my life but he was a very violent narcissist. And so some of my earliest memories are pretty violent. My mother had me when she was 18 years old, so she was a child. It must have been incredibly hard. Me and my mom have a good relationship. She’s one of the greatest poets I’ve ever known. She’s just an amazing poet. She raised me up around art and expression. I think the first time I did a poetry reading I was like six. It was a Mexican restaurant that also had poetry readings on the weekend, they had a live jazz band. I read my poem when I was six with this live jazz band and it was something about my imagination. A very childlike poem. That was a cool memory.

And then the same night my mom got too drunk and went onstage, and they had a Crypt Keeper Budweiser standee. It was the Crypt Keeper from Tales of the Crypt and he had a Budweiser and was like, “drink Budweiser.” And she went onstage really drunk and grabbed it – I guess she didn't like the way the audience responded to her poem – and she was like, “this is the devil that lives inside all of you fucking people.” And she ripped its head off. So she got arrested. And I was just sitting at the bar. They took her away and then the bartender realized, “oh this is that lady’s kid.” So I’m just sitting there and he was like, “Do you want some fried ice cream?” And I was like, “hellyeah.”

My life was always chaotic in that way at an early age. For every brilliant thing I was exposed to there was some bizarre, fucked up thing that I also got exposed to. I was a child who was sort of treated like an adult. When my mom and her friends were around discussing films or shit, they included me in those discussions even though I was a six or seven year-old. I remember they were talking about how good The Shining is and I remember being like, “Oh, I’ve never seen it.” Of course I’ve never seen it, I’m fucking seven. And they were like, “Oh, we got to go rent it.” So we rented The Shining and it was scary as fuck. It scared the fuck out of me. And what scared me the most was that scene where the guy’s getting blown by a bear. If you’re a child and you see that, you really don’t know what the fuck [that means]. I don’t know what that means now, as an adult.

But I am grateful for those things because I think it’s made me have this love of all kinds of art. She gave me a love of every kind of art there is. I’m really open to almost any kind of music or movie or book. My tolerance is pretty high for weird shit. With music, I haven’t heard a band – yet – where I’m like, “Oh no, this is too weird for me.” Which is cool because as you get older you really start getting scared of new shit. Like, I sent you that Father Abstrakt song by that kid. And it’s so beautiful because everything about the mix is wrong. It’s blown out in a way that sounds like it’s coming from a Nokia phone from like 2002. It’s the weirdest shit I’ve ever heard. But when I first heard it I was like, “Oh yeah, of course. This is what new music would sound like. This makes sense.” Or like Jane Remover or any of these bands that are doing this very wild shit that's in your face.

Earlier you said you had PTSD. Did that have to do with your dad?

Some of it. It’s a weird thing because it’s not like I wake up in a cold sweat from some specific nightmare. I just feel a general sense of panic at all times. I’m always in fight, flight, freeze, or fawn. Growing up in poverty is a very dangerous place for anyone to be. It’s a dangerous lifestyle, and I think that had a lot to do with it. And these things compound themselves. People who are traumatized as children go on to experience trauma later because they get caught in the cycle. The cycle of abuse can be something you perpetuate onto someone else because of a learned behavior, or it can be what you allow yourself to be perpetuated onto you over and over again because it’s what you're used to.

Do you feel like you’ve experienced both ends of that?

Yeah, I think in some ways. I think that it took me a long time to learn how to undo some of the maladaptive thinking I would have, or behavior. I always wanted to make people happy and be a comfort to others, and I never felt like I needed to get revenge on the world or anyone and cause pain the way I felt pain. I always wanted to contribute something nicer to the world. But especially living this music world I fell into…because I never really had any intention of doing any of this shit. I didn’t really want to be a musician or a songwriter. My first dream was to be a filmmaker. I wanted to go to UCLA and be a filmmaker.

I read the biography of The Doors called No One Here Gets Out Alive when I was like 10 or 11, and I was like, “I want to go to UCLA and be a filmmaker like Jim Morrison.” But my grades were horrible in high school. I had a 0.7 GPA when I dropped out of high school. I would go to class and just sleep.

What made school so difficult?

I got in trouble all the time. Minor stuff, but I couldn’t really thrive in that environment. I’ve always had a sense where if I feel wronged, I’ll go into full on fucking Bugs Bunny revenge mode. Like the way he would always fuck with Elmer Fudd and stuff. I go into that person, or like The Mask or something. But it’s me lashing out. I would do that a lot in school. At one point I just gave up and I’d come into class with my headphones on and just lay my head on my desk and listen to CDs. None of the teachers would even try to wake me up or get me to participate.

That was a couple weeks before I dropped out. And I don’t really regret dropping out. I do think it would’ve been cool to go to college and have that experience, and I think it could’ve helped me in a lot of ways. But it just didn’t happen for me. I dropped out and then I started devoting myself to music and playing shows and forming bands. That kind of became my entire life. And then I woke up 12 years later and I was like, “Oh, what the fuck happened? How am I here? What is this?”

A lot of what I’m asking you is going off of lyrics you’ve written and things I’ve seen you post over the years. On Loss Memory you sung about being drunk in your car when you were younger. Were you doing a lot of drugs and drinking in high-school, too?

Not in high-school. Especially in that song…I did go to community college for a short time, but then I had started drinking. I didn’t drink much in high-school or really do any real drugs. Which I’m glad, because I was crazy anyway. Like, I’m a crazy person on some level. I have diagnoses, and part of me is very skeptical about the psychiatric world.

Why is that?

It’s only been around for a short time, psychology. And I do think there’s a lot of cases of it being used to harm people in a class way. So I’m skeptical of it, and it hasn’t helped me much. I had some pretty bad experiences with therapy when I was in high-school, where the therapists were either creepy or had a disdainful attitude. I avoided [drugs and alcohol] until my early twenties and when I started drinking I just went full-in. To be able to turn my mind off was incredible. I didn’t have to think constantly and constantly be afraid that something horrible was going to happen at any moment. And to not have a good thing happen and then immediately be like, “Where’s the receipt? Where’s the bad thing?”

I used to fill up a Dasani bottle with vodka and I’d sit in the back of my community college class and I’d just be fucking drunk. Like, so drunk, and I’d be answering questions. I had to be the most annoying…because when you’re drunk, you think you’re real cool. So in my mind I was like, “Hey, what’s up teach.” I had to be insufferable – with sunglasses on. Just a total fucking idiot. But I did have a public speaking class that semester and I got straight A’s in that fucking thing.

So you could always get up in front of an audience?

Yeah, even as a child. But what was weird was when I started playing shows I used to just vomit before every show, for like a year.

In high-school and as a kid, did you have an easy enough time getting along with people outside of your family? Like friends, schoolmates. Or was socializing difficult for you?

I had two or three really, really close friends. I wasn’t a popular person. I was known for being funny, I was known for being weird. And it wasn’t cool to be weird then as much as it is now. When I was a kid, I used to wear a Radiohead shirt to school and I’d get made fun of. They’d be like, “you always wearing some shirt for some bullshit nobody knows.” It wasn’t cool to like underground music then. You’d get bullied for that shit. And like, wearing thrift store clothes wasn’t cool. I did a lot of those things. I was definitely a hipster kid. I listened to Elliott Smith and Neutral Milk Hotel.

A lot of my friends were in the 12th grade when I was in the 9th and 10th grade, and then they left, which left me kind of alone. I probably started acting up more then, because I lost my friend group. I’ve always hung out with older people, until I became the older person. That was kind of a funny thing where I realized, “Wow, I don’t have as many older friends now. Now I’m the old fucking guy.” It’s important to me to never be the old guy that's like, “Oh yeah, my shit is cool. My movies are cool. My records are cool.” Because that's just bullshit. A lot of people my age are so weird about shit. They're obsessed with cartoons they watched 25 years ago.

Oh yeah, I hate millennial nostalgia so much.

It's definitely a cultural poison. It just allows capitalists to exploit us as much as possible. Preying on our memories. People don’t make new things as much. Especially in film, because they know they can bring back some fuckin, ‘Here’s Alf! Remember Alf?” And you’re like, “Oh, cool.”

There’s a lot of references to Christianity and religion in your music. Was that a big part of your life growing up?

Yeah, for sure. My grandmother, bless her heart, is an extremely paranoid kind of person who’s obsessed with the End Times prophecy type of stuff. We would watch the show Jack Van Impe all the time. It would come on late at night and he would basically just say the news and then quote bible verses from Revelation that aligned with the news. Like, “Russia is the great red dragon. Russia is gonna rise from the east.” The bible has a lot of fucked up words in it. There’s a lot about the Whore of Babylon in Revelation. So I’m a little kid learning about the Whore of Babylon and how she has blasphemies against God written all over her body.

My grandmother was also paranoid and into the Satanic Panic stuff of the 80s and 90s, and she used to tell me that people would climb in my window and kidnap me. I remember one day me and my mom got an apartment on the second floor of a building and I was all happy and shit. I was like, “Grandma, guess what? We got an apartment on the second floor. That means nobody can climb in my window and kidnap me.” And she was like, “They’ll just use a ladder.” And I was like, “fuck.” I’d be up all night, I never got sleep, because I’d be listening for a fucking ladder.

What would she think you were going to get kidnapped for?

This is when I was a little child, and she would graphically say that pedophiles would kidnap me.

That's terrifying.

It was pretty scary. And I was pretty paranoid all the time. But the religion…I really love religion as an interest. I have an academic interest in all of it. I love watching…I can’t remember the name of pastor, it’s this Canadian, very leftist church, and they go through the Bible in an academic and historical way. It’s really illuminating and fascinating stuff. It’s something I’ve read a lot about since I was a little kid. I’ve read the Bible a bunch. I definitely don’t think that the Christian god is a real entity in the way that we would perceive it as being either vengeful or redemptive.

You had a good relationship with at least one of your grandfathers as well, right?

Yeah, on my dad’s side. He kind of raised me from like 10 to...I think I moved out around 19 or 20.

You weren’t living with your mom at that point?

No, she wasn’t really able to take care of me. She had her own issues and he took me in. He was a really, really hard working guy. He grew up so poor. Like, his family used to have to scavenge coals that would fall off of the train, like fucking Angela’s Ashes, to heat their house. He had eight brothers and sisters. He worked his whole life, from like the age of 10 or 11. He dropped out of school in fourth grade or something and worked HVAC his entire life. He was an interesting guy. He was a very masculine guy, he was definitely a rough, blue collar guy. But he also was extremely sweet and emotional and loving. I didn’t have a toxic masculinity influence from him. We’d kiss each other on the cheek, and when I started painting my nails in high-school it was never any kind of issue.

I remember I used to wear all black and paint my nails and wear makeup and my grandmother didn’t like it but he was like, “Well, Johnny Cash wore all black, it’s cool.” That made me think it wasn’t cool. I was like, “I don’t wanna be like Johnny Cash, I want to be like Davey Havok from AFI.” He was a sweet man. He always encouraged me. I’m blessed to have had my time with him.

So he was your main patriarchal influence?

Yeah, and I have a good stepdad. My stepdad was super into college rock and he bought me a lot of great records. He got my Replacements Tim when I was like 16. And Let It Be. He was like, “you’re at the right age, this is the best record you’ll ever hear.” And he was right…So I had some pretty positive men in my life. I didn’t really need my biological father, and I’m lucky for that. Because if he had been the sole example it probably would’ve done me a lot of harm.

Was he still around in some regard throughout your teen years?

He would show up to belittle and be weird and an asshole, and then he would disappear. We never had a good thing. He was someone who would never support himself. My grandad paid his bills all the way until [my granddad] died. He was sort of a freeloader. When I started making music my dad was very discouraging. He’s a musician himself but he basically just plays Ted Nugent riffs. But he always had thousands of dollars in gear and cool guitars and I had bottom of the barrel shit that I scrounged together. I’m glad for that because I learned so much more about making art having to really struggle to make it. If I wanted a sound I'd have to be like, “How the fuck do I get this sound?” Instead of just, “Oh, I’ll plug in my expensive gear and it’ll make the sound.”

And I do wonder now with the way things are going, where you just sort of pseudo-AI some shit, if people will lose that spark. I hate, and I know you hate it too, when these tech bros come in and they say, “No one likes being in the studio all day tracking the same shit over and over, the AI will do it for you.” But people do like that shit. People do like the process because it’s real and it’s your whole mind and body. It’s a spiritual thing. These people have no fucking soul, that's the problem.

So you wanted to be a filmmaker but you started getting into music. Tell me about the beginning of Coma Cinema.

I’ve used the same recording machine on almost every record I ever made. It’s a Korg D3200, 32-track digital work station, which no one really uses anymore – for good reason, because they're very clunky and obtuse. But I bought that with my first job. I was 15 and I worked at Publix for $5.25 an hour, which was the minimum wage at the time. I saved up all my money, I bought the Korg D3200, and then I spent four years making what would become the first Coma Cinema album, Baby Prayers, which originally came out in 2009. I used to play shows in my hometown but nobody got it, everybody thought it was bad. People would tell me that I needed to quit. Maybe it’s not this way, but I feel like people were much harsher back then. If you were trying to do something and it wasn’t perfect, people were like, “Oh, you suck, you should quit.”

And I think indie-rock then…there wasn’t like a lo-fi movement. Everybody was in the fucking studio. You had Grizzly Bear with their records sounding like a million dollar record, and “indie” just meant “less popular.” Because they had the same fancy studio setup for the same kind of sound. So when I was doing stuff, it wasn’t like I was trying to be lofi. I was trying to be hifi. That's why I bought a digital machine and didn’t get a tape machine. I didn’t want sound like Daniel Johnston. I wanted to be taken seriously, and that was very hard.

But I made that record and I used to hand out CDs everywhere. I used to just go downtown and hand out CDs to people. I went to Canada for the first time when I was like 19 and I brought a bunch of CDs with me and I was in Montreal trying to hand people CDs, but they thought I was trying to sell them. So I had to ask somebody, “how do you say free CD?” That didn’t really go anywhere. I mailed demos to all the labels. Merge, Kill Rockstars. I mailed this weird shit. I had these pink boxes that were filled with these little plastic skulls that I had painted pink, and I had some dollar bills I’d cut up into confetti, and I put that in there. And I put sleeping pills in there, and then the CD in there. And I sent it all to the record labels and I was like, “This’ll get me signed.”

There was no rules. There was no, “here’s how you make it.” There wasn’t even – what is “make it”? Because back then there was no way that you as an indie artist were going to have a career. That was an absurd thought. You just wanted to make art and have people hear it for some strange reason. And then Myspace came around, which is cool. And that's how I met people like Rachel Levy and a lot of people that I’ve collaborated with over the years. And then Chaz Bundick, Toro Y Moi, he started to really take off. I used to play shows with his band called Heist and the Accomplice. It was an indie rock band. They would let me open as Coma Cinema. He really liked my stuff and was very supportive.

One day he sent me a message on Myspace and was like, “Yo, you gotta send your music to music blogs, that's what I did.” And I was like, “OK.” I didn’t know what a music blog was. He was like, “Here’s a list of them.” And I sent it to every one on the list and I probably wrote something psychotic in the email. You’ll have to remind me to tell you about when I was trying to get everyone to listen to Alex G and I sent all these psychotic emails to all the music writers I could think of, like Ian Cohen and shit. I was writing emails like, “This is Alex G, it’s gonna be the biggest music in the world, if you don’t fuckin’ put this shit on right now you’re gonna look like a fuckin’ idiot in two years.” Just really aggro. Because I was pissed that people weren’t listening to him. Now he’s a superstar, as he should be.

I was sending emails and one blog did post [Coma Cinema] and it went from there. I made a music video for “Flower Pills” that took three months and I lost my mind making it and that got on a bunch of websites. From then, I had listeners, and I still have some of those listeners to this day, which is fucking nuts and really beautiful to me.

I want to get into that era more in a second. But in terms of your musicianship, you’re a multi-instrumentalist, but I’ve always thought of you as a bassist first. You have very melodic basslines in your music. Do you see yourself in a similar way?

Yeah, I think I definitely love the bass and I love music with great basslines. I was really sad to hear about Sly Stone the other day even though he was fuckin 82 years old or whatever. Because his records are so phenomenal. You take There’s A Riot Going On, there’s so many great basslines on there, and I would never have been able to do the kind of stuff I’ve done if I hadn’t been turned onto that. And Prince was one of my first favorite artists. It was either Prince or Michael Jackson.

I definitely am a melody-first songwriter. I write most songs without instruments. I wrote most songs by kind of mumbling to myself looking like I’m in fucking One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or some shit. People ask me all the time, “what’s some advice for writing songs,” and it’s too open-ended, but just going on walks and singing to yourself. Lyrics, too, are the same way where it’s all rhythm, it’s all syllables. It’s all that rhythmic way of speaking. It doesn’t even really matter so much what you say, it’s the tempo and rhythm of which you say it, I feel. And bass is a lot like that.

It’s cool that you dig [my basslines]. I put a lot of focus on that. Some of the basslines are fucking hot. One day when I’m dead people will be like, “Damn, there’s some pretty good basslines on this shit.” Like Depressedica. There’s some good-ass basslines on there.

Definitely. And obviously like “Weird Honey.”

You know what, I didn’t write that one. My friend Eric Jones wrote that one. So I can’t take credit for that one, but we both got really into the bass guitar together and were both very into the idea of playing high on the neck and doing lead on bass.

I was reading an old archived interview from 2011 where you say that you were very insistent about not making money from Coma Cinema. You were saying earlier that you were giving away your CDs. You were giving away your music on Bandcamp, and in that interview, you were even saying that you were trying to convince your label to put your cut of the profits into more vinyl pressings. So not only did you think it wasn’t possible to have a career in music, as you said before, but at first you didn’t even want to try. Why was that?

I think that was an era where selling out was something that existed. And then as I grew older I realized that this narrative of selling out being inherently bad was a capitalist trick. Like, “stay poor and keep your integrity, but stay poor. Because then you can’t do anything. You can’t really have a voice.” In a capitalist hellscape, you have to have money to have a voice. I think I really wanted people to know I wasn’t bullshitting about this being art. Like I was saying earlier about bands at the time, there was sort of a “trying to be professional or hifi,” and I wanted to be more punk and all that.

But that was much easier of a mentality to have when I was young and my only needs were liquor and a twin-sized bed. And I didn’t have cats or people in my life that I wanted to protect and take care of. I had a more fatalist perspective where I was sure I wasn’t going to live that long anyway. So why make money? Why do anything except express yourself? I really wanted there to be no barrier between someone listening and someone wanting to listen. And at the time it was pretty rare to see people offer their music for free, which is strange to think about now because everything is essentially free.

And I think it paid off in the sense that people were able to hear the music. I used to have a website that you could just free download off of, and at one time, I was getting a lot of hits on that website. Now, it’s crazy to even think that someone would have a website. Everybody’s on a different kind of platform.

You said you didn’t think you were going to live that long. Why did you feel that way at the time?

I just didn’t have a desire to live that long. I didn’t really want to. I guess I sort of glorified the “die young” mindset of art and punk and shit. I didn’t even have a concept of death all that clearly then. My entire goal every day for so long was to make the panic stop. To turn my mind off, by any means necessary. And so I drank a lot. I went really hard. I did dangerous things for fun. Or not even fun, but just for the fuck of it. Climbing on shit, hanging out of cars. Sort of testing the boundaries of reality and testing fear.

I haven’t thought about it too much but I guess when you’re afraid all the time there’s different ways of coping with it and maybe one of them is doing things that are scarier than your thoughts. Like, my thoughts are terrifying, but maybe if I get insanely drunk and hang out of this moving car, I’ll be scared of that for a moment. And that's a lot less scary than this panic I feel. I don’t think I was alone in that era. I think there was a lot of nihilism, maybe you’d call it, or no fucks given. Or what was it, “YOLO”?

And then a few years later is the SoundCloud rap era, where that sort of becomes mainstreamed in a way once again. This glorification of death and depression.

Yeah, what was Carti’s [album title], like Die Young?

Yeah, Die Lit. And he was one of the few who made it out.

Right. And that's a sad thing. You realize that as you get older when you lose people to…there’s not a single person I lost to drugs or alcohol who I don't think was a deeply good person who was trying to just feel OK. And unfortunately they're not here now and that's sad. Because on the other side of that, there can be peace. There can be a peace that comes from just being alive and being in your garden or something. There can be that kind of relief from these anxieties. But it doesn’t feel that way when you're young. Everything is immediate and everything is forever feeling. And you don’t have the broadness of perspective. Yeah, there's a lot of people I wish were still fucking here.

So your record Posthumous Release, that title wasn’t a joke. You were speaking to an imminent death that you were feeling at the time.

Yeah. It’s still a joke because it’s that gallows humor thing, too. You want to laugh it off. And also it’s somewhat genuinely funny to be given the gift of life and then want to die. It’s a little funny in itself. I’ve always really loved Warren Zevon, who is extremely funny but also very bleak. And I really liked that, and I really relate to that. In the new record, the last line is, “Find humor in despair.”

Yeah, this is a huge motif on the new record.

That's sort of my philosophy in a lot of ways. It’s a better coping mechanism than numbness. Numbness won’t make you laugh. It’ll just make you numb. And laughter is a really powerful high. I don’t want to convey a message of not giving a fuck. I think it's, like, laughter out of a deep connection with something rather than being disconnected or turning it off. You have to really live in a moment to laugh at it. Whereas numbing yourself is definitely disconnection. We do have to try to live a better life and create a better life. It won’t just happen to you. But you can have some laughs while you’re doing that so that you don’t go crazy.

The early Coma Cinema stuff was very singer-songwriter based, as opposed to the early Elvis Depressedly, which was pretty much droney, instrumental noise-pop. Save the Planet Kill Yourself, specifically. At first, was Elvis Depressedly intended to be this very separate artistic project?

Yeah, definitely. It’s funny to think about now but I got so scared when Coma Cinema started to get kind of popular. There was also this situation where in my hometown, the same people that were like, “you should quit, you suck,” were now like, “you’re a bad person because you’ve gotten success.” There was a lot of backbiting and anger that it was me who was getting attention, because in their minds, I was awful. I made bad music. Why is my music getting attention and not their music that sounded like Gin Blossoms? It was a bunch of old-heads and they were mad as fuck. So I got real paranoid, I didn’t want the attention on some level. But I also really loved it in some way.

And then I said, "well I’m gonna make another project." Well, I had the other project because I did the drone record, which is just something I wanted to do because I liked that kind of music. And then I was like, well I’m gonna start putting all of these songs that were going to be Coma Cinema songs into this other project that no one listens to. And then I won’t have to deal with these fucking people and I can be more vulnerable and not have to worry, “are people gonna like this song? Are they gonna think it sucks? Are they gonna be like ‘the old shit was better'?”

I didn’t want the pressure, so I started making those indie-rock Elvis Depressedly records and lo and behold, that shit got way more popular than the other shit. No one gave a fuck about Coma Cinema, and then I was in a worse situation at that point. Holo Pleasures… I made that and Posthumous Release at the same time and they sound so different. It got very nerve-wracking. I used to get death threats all the time on Tumblr.

For what?

At that time on Tumblr, if you had any kind of notoriety, even a small level, there would just be drama. And there would be people who said they wanted to kill you. And I would always be like, “Alright, come kill me. Let’s see what happens.” But no one ever did. And I used to be very opinionated on there. I used to say shit because in my mind, no one was reading my shit. But then a lot of people were reading it and I was talking shit about whatever the fuck. I don’t talk so much shit these days.

Really? [skeptically]

Yeah, less. Mostly because I don’t have as many opinions, really. But I used to get on there and I used to get very angry about bad art or something. Like when every band started to sound like fucking New Order. I was real mad about that. I was like, “why the fuck is every song about going to the beach? Why is every fucking band just New Order? This is bullshit. We should collectively, as people, try to make better art than this.” And then those people who made that shit would get very mad, and they were like, “I don’t even know who New Order is. I just made this because I like chorus pedals.”

Nowadays, I try to assume, if I hear that kind of music I’m just like, “they’re just kids who like chorus pedals.” That's all. They're not derivative intentionally. But I used to go on rants and stuff. It never benefited me to do so.

You said earlier that you never considered yourself someone who wants to inflict pain upon others or be a vengeful person in that way. But it seems like you’ve always been liable to be provocative. You’ve liked provocation, in one way or another, for most of your life.

Yeah, it’s definitely a game that I’m sometimes playing inadvertently where it’s like, I can’t help myself. It’s the call of the void, but a social call of the void. Where you just want to say something provocative…it’s essentially somewhat like trolling. But I always believe what I say, at the time at least. I might wake up the next day and be like, “Oh god, why did I think that?” But I always think that at the time. I was really scared when I put out that song about Casey Anthony, but I think she’s innocent. That's just me.

Why do you think that?

I don’t think she killed her child, from watching the trial, and the jury didn’t either. But that's just one thing I said that was maybe a little crazy. And I get manic, and I start maybe connecting dots that aren’t there. Yeah, I am liable to say weird shit, but I try to do it with joy in my heart these days. You should always post with joy in your heart, otherwise you’re going to be in trouble. You don’t want to get angry. Because it’s just not a good attitude to have, especially with the internet, which is designed to make you angry.

I think that DIY in my era was very backbiting, and people were not happy with each other. They were very jealous of each other, no one wanted each other to succeed. I was never like that. When I would find a band that I thought was great, I would champion that band more than my own. I would hype them up like fucking crazy. I did that so many times and, to me, that was the greatest part of having an audience. Putting people on to new shit. I wanted to change the culture. I wanted to change that rich kid, hifi culture by getting people to listen to real shit made with real heart. And I think I was successful.

I look at the landscape now and I see so much more honest, heartfelt expression. Not a lot of put-ons, not a lot of Too Cool for School kind of bullshit. Just people saying their truths over music that sounds like their real emotional power. Now, I don’t see a lot of faking. You get it every once in a while. What’s that band, The Dare? Do you like that band?

No.

Yeah, I don’t like it either. That sounds like the shit I used to hear in 2003 when I was coming up. Where some guy with bright Ray-Bans and tight ass jeans is being like, “pouring whiskey on my dick, so I can suck myself off.” It’s the worst shit. But that's not coming from the heart, and I don’t think [The Dare] would say that. I think if you interviewed them – and you should – they would not say, “this is my heartfelt expression.” Party music for party boys.

You said Toro y Moi took you under his wing when you were coming up, but were there any other artists who you were part of a community with in your early days?

Yeah, all that Orchid Tapes stuff was huge. We really had a movement going. We did shows in L.A. and New York that were sold out. Where like Rachel Levy, me, Happy Trendy…and the cassettes thing, I feel like that was a big part of bringing that shit back. It was a real beautiful time. It was very collaborative, loving, supportive. And I loved Orchid Tapes because I could find a band and get them on Orchid Tapes, and it would sell out. I basically worked A&R for that label.

Were you being paid?

No, I wasn’t paid. I also did that for Run For Cover. I was their free A&R guy. I was supposed to get paid by them but I never did. They owe me $60,000 right now. But you know, what are you gonna do? Gotta tickle them if I see them. I’m gonna hold them down and tickle them until they give me my money. If I could tickle them and a dollar would pop out every second, that’d be nice.

But I loved doing that. I loved finding new music. There was a time in my life when music was so much of everything. I would go on Bandcamp and click on the “new releases” thing and you would see a live feed, and I would just refresh it all day long. And if the album cover looked cool, or if it looked like it was really fucking weird, I would listen to it. I may have found Alex G that way. I either sound Alex that way or Rachel Levy sent me his stuff, it was one of those. We were always passing stuff back and forth.

It’s harder for me now, I don’t spend 24 hours a day listening to music like I used to. I used to literally do nothing else. I still love music and still try to keep up with it, but the vibe is different. I’m sure there’s these kind of Orchid Tapes style subcultures out there, but I’m not in them because I’m an old person, so I don’t know about them. So I don’t have that daily community of, “did you hear this? I’m working on this.” It’s very solitary now, which is how it started. I’m just making things by myself and I’m not really part of a scene. I have my listeners and I’m in my kind of bubble. It’s a great bubble to be in.

Like my friends in TV Girl. I love those guys. They have a crazy amount of fans, a billion streams or something. Some of the stuff I see [regarding] their fans and the way they interact with their music is strange to me. Any artist that gets to a certain level, you start seeing these weird…I hate to say parasocial because that seems so negative. A lot of times it’s just weird kids being weird. When I look at it I’m like, “I don’t even understand what’s happening here.” I’ve never listened to a record this way where I’m making these bizarre memes and stuff. But that's just the culture.

I’m glad with where I’m at because I can have these connections with people and they know I’m just a person, and they don’t treat me weird because they know I’m just some guy. There’s not that wall of mystery there that fosters that strangeness of what might be parasocial or something. I don’t really have to deal with a lot of that, which is pretty good. Because my mental state…I can’t handle anything like that. I would crash out so quickly if I had too much attention. It would be insane. I would end up burning to death somewhere.

You grew up in a pretty poor environment, you had mental health problems, you’re a weird guy. When you joined that scene in the early 2010s and became involved in the music industry, would you say it was difficult for you to integrate in those spaces because of your relatively strange background compared to a lot of other indie rock types?

Yeah, for sure. Especially the higher I went up the ladder. I realized pretty quickly that I was the only poor person in most situations.

That lofi movement was very important to me during my early twenties, and it was a lot of middle class kids – I’d count myself among them – kind of playing poor. Bands making their music sound shitty aesthetically, but there was also this romanticization of wearing shitty clothes and listening to this sad, dingy music. And a lot of that was being enjoyed by kids like me who didn’t come from those circumstances. Was that weird for you to partake in?

I think that's OK. I think all culture comes from poverty up. I do think that on some level, not real art, but art that really touches people comes from a certain level of pain. In the best sense, it’s about overcoming that pain. And I think people feel it and they want to be a part of it cause it’s real. I think that's OK. I definitely think that there was a huge disconnect between the other artists I would meet.

I never had a manager in my life. I had a booking agent for a while, but I couldn’t relate to a lot of those people and they couldn’t relate to me. And I was a little bitter about being around those types of people because it was so hard to get where I was and I did feel like they didn’t struggle enough, and I did feel like they were less authentic because they didn’t struggle. But I do think sometimes that's a poison way of thinking because everybody has their own struggles.

Someone like Clairo, who I think is a great artist, obviously had industry connections, but she also grew up with rheumatoid arthritis. That's a horrific, horrific struggle that most of us can’t comprehend. Everyone has their own horrible thing they're overcoming. But you’re right, it was hard to deal with. And I didn’t like being at those fucking Los Angeles parties in these mansions. I didn’t find myself having a good time and a lot of those people I met were pretty bad people.

I do think growing up rich, and I don’t even mean middle class or upper middle class, I mean fucking rich, deprives you of some humanity or something. Because I met a lot of really vicious people. And I guess you have to be somewhat of a narcissist to have that kind of money and not just give it all away. Like, I would definitely get mine and have some stupid expensive clothes, but I can’t imagine myself having a million dollars. I would just give most of it away to people I know and stuff. I wouldn’t want that on me. But these people have a hoarding mentality and a circling the wagons mentality, and there was always a sense [that] I wasn’t allowed or I wasn’t supposed to be there. I was not one of them.

These are musicians in indie rock?

Yeah, musicians. A lot of time label people, managers, publishers, publicists. A lot of slimy people. I remember being in these rooms with these people and I’m like, “why are they all doing this fucking act?” They know the stereotype, but they're all being that slimy industry stereotype. It’s like they just assumed that role, and because they're rich they can just have that role. I knew I could never hang there long.

What era was this?

Definitely like 2014 to 2018, 2019. Before I stopped touring.

In terms of your access to the industry, that was your pinnacle of being invited to those spaces?

Yeah, for sure. I toured with a lot of artists that were on the come-up, sometimes because I was wanting them there, and sometimes because it was just what I was told to do or what those artists were told to do. Like, I don’t think Mitski would have ever chosen to tour with Elvis Depressedly. I know, because I had conversations with her, that she despised the people who'd come to her show. She despised them. Because in her mind she was a composer for high-end, Broadway rich people music. So to do this indie-rock shit, I don’t know if she [maybe] felt humiliated by it.

But she was a really interesting person. I wouldn’t say we didn’t get along, but she’s from a different universe than I am and we couldn’t relate to each other on any level. I saw a lot of that in bands, the contempt for their audience. Which I never understood. I love everyone who listens to my music, they're all very nice people. They come up to me and they pour their heart out to me, and I love them, truly. I’m grateful to them.

You’d be surprised how many bands hate their audience. Usually for shit that's their own fault. It’s like, you made the music that attracted this audience. If you wanted to make high art, you should’ve made high art and had an audience of three people. If you make something that appeals to all types of people, you’re gonna have a lot of types of people around you and you got to be open to it. But a lot of these people hate their audience and they're frustrated and it’s weird to me.

You got to curate the audience that you can be honest with so that when you do the stuff they like they come along with you – or they don’t. They’ll get you on the next album. “That one had too much auto-tune for me.” A lot of people in indie music think they're better than other people. And I think a lot of it does come from a classist privilege, but also, art communities have always been gatekept from certain people in an unfortunate way. And sometimes people break through that, and when I did, I didn’t like what I saw and I was happy to be away from it.

You had this brush with that world and I imagine that created a sense of disillusionment. Did that sort of manifest in self-sabotage, would you say?

You may be right about that. I was never the type of person where if they told me to do something…if I didn’t want to do it, I wouldn’t do it. There was probably a lot of times in my life where I could’ve met certain people…like, I met Bob Boilen from NPR and I was drunk out of my mind. If I had been real nice, maybe I’d be on Tiny Desk. But because instead I was like, “nice hat!” Maybe made fun of his hat a little bit, there [goes] that opportunity.

I just didn’t want to play a fraudulent game. I wanted everything to have a purpose and be artful. I didn’t want to gladhand and all that kiss-ass stuff. Not to say I never did. There’s certain amounts of money where you’ll do almost anything. But I didn’t want to be false, I wanted to be true. I’m sure I self-sabotaged a bit. When I was touring with that band Turnover they tried to pull some shit on me a couple times.

One time after the show I hadn’t gotten paid yet and I’d been waiting around for like two hours, and I’m looking for the promoter and I’m like, “I need to get my money, this is crazy. I got to get to a fucking hotel, I don’t have a tour bus.” So I’m going around and I asked the [Turnover] bass player, “Hey, where’s the promoter? I need to get paid.” And he’s like, “Oh, I got your money right here,” and flips a quarter at me.

What the fuck.

What you’re supposed to do in that situation, if you’re career-minded, is be like, “Oh, man. That's a good one. I guess I’ll go look for the promoter now.” But I threw the quarter at him and I said, “What the fuck is your problem? You don’t throw a quarter at me, I’ll fucking kill you.” Like, don’t do that to me, don’t treat me like that. You’re not better than me. I would never allow shit like that to happen – and you’re supposed to. You’re supposed to be cool with everything. But I never took disrespect like that. I didn’t feel like I would feel good. Like what, if I lie to myself and I’m cool with this asshole, I get to be this asshole’s friend? That's not a reward. That's a shitty existence. I’d rather this guy think I’m an asshole than be around this fucking guy.

And the other perspective would be, “it’s not a big deal, it’s a minor joke.” And the person who would say that would probably be right. But I grew up in poverty. I grew up with people all my life making me feel less than because of how much money I had. So in that moment, that shit is very triggering. Everything in our lives leads us to everything that we do and how we react to things, and the shit I went through just made me not cut out for the music business at that time.

It’s interesting because I found your music from Run For Cover, because I came from the world of Turnover and Citizen and those bands I listened to in high-school. I’d listen to anything that label put out, so they put out New Alhambra and I listened to that shit. So you probably did gain quite an audience by participating in that world that was a little separate than the Orchid Tapes world, the self-released on Bandcamp world. But do you think that period of your career ultimately did you more harm than good?

If I could go back in time I wouldn’t have taken the [Run For Cover] deal. My record contract wasn’t for much. I think I signed to Run For Cover for $2,500. But I was so desperate for money at the time that I was happy to do it. And there was no other label that even gave a fuck about me.

Why is that? Because you had so much hype at the turn of the decade.

I don’t know why. I’ve gotten coverage at certain places here and there, but it was always because a specific writer liked me. From everything I’ve ever heard, the people in charge of these websites didn’t want me on them. I don’t know why, and labels had no interest whatsoever.

Did they think you were a liability because of your personal behavior?

I guess, but there wasn’t really much of my behavior then, unless just being a drunk…

That's most of the music industry.

Yeah, [that's] everybody. I’ve never been a danger to anyone but myself. So I don’t think that had much to do with it because labels love a drug addict and a drunk because they can milk that person until they die young and then they can milk them forever. They love that shit. I’ve been told before that there was an idea that I would never even entertain an offer, so no one gave me one. Like we were saying earlier with the, “I don’t want to make any money or whatever." Shit like that made people think that I would tell people to go fuck themselves. Which wasn’t true. I was always willing to entertain an idea that helped the music be heard. And I wanted to make a living, I wanted to survive.

Run For Cover was the only one who reached out and I took that deal. Wasn’t for much, but if I could go back I wouldn’t do it because I wouldn’t be involved in a situation where they're keeping a bunch of my money that they're not entitled to. And they used me a lot. I did a lot of A&R for them. I facilitated a lot of stuff between artists that signed there and the label, because they were a good label for a time. But now they don’t do their own payroll, they have a company that does it. They don’t do their own distro, they have a company that does it. Everything’s outsourced.

It’s a situation where the original guys at the label are on vacation all the time and they're living that lifestyle, but they don’t really do anything. It’s all outsourced to different people and interns and stuff. It became a big machine and they sort of lost the plot. And that was sad to see because I believed in them for a while. I believed that they were doing something different. Turns out they were trying to do what’s always been done, and that was kind of a bummer.

They're not paying you royalties, is what you’re alleging?

Yeah, our contract was supposed to be over years ago but they kept me in it. Basically what happened was they had one more option in my contract, and if they said no to the option it was supposed to end the agreement. And they said "no" to the option, and the agreement is ended legally, but they just continue to collect and host my songs and sell records of mine, and they don’t have a right to. But that's a situation I’m just gonna have to navigate when I get the chance. At this point, I’d rather focus on continuing to make records and be in Coma Cinema, and stuff like that.

The only part that really hurts me is it’s made me resent those albums, which I don’t want to do. I’m not the kind of person that's like, “Oh, I’m so embarrassed about that thing I made.” I stand behind everything I made and I hate having that resentment for those records because they do mean a lot to a lot of people, and I want to be able to see them in that way too. But I’ll get there…and it’s funny because Coma Cinema is now more popular than it’s ever been, whereas Elvis Depressedly is probably the least popular it’s ever been. Part of me is gleeful when I see the numbers go down, because I'm like, “Hellyeah, less money for them.”

How much money are you making from music in general? Are you able to live off of it?

Yeah. Meagerly. But I can pay my bills. I got into a lot of debt during COVID, like a lot of people did. And Helene and everything, I’m working my way out of that. But I can survive. But it takes a lot. I have to do the merch game, pressing vinyl. It’s one of those things where if one thing were to go wrong, the whole thing would fucking collapse. But so far it’s been OK. Sales are steady and like I said, Coma Cinema is more popular than ever. Which is not that popular in comparison to other bands, but popular enough. It’s in that sweet spot where I can make a working class living and I don’t have to lose my entire mind doing it by being too known.

And you know, I’m really proud of Elvis Depressedly as a whole. There’ll never be another record. I know I said that about Coma Cinema, but I really can’t see going back to that thing. It’s also such a time capsule. The name is very funny to me, it’s a funny joke. But it’s very of the time. People used to get so mad about that name. Because I’m like, "who are you mad on behalf of? Are you mad on behalf of Elvis? I don’t think he cares. Are you mad because it’s a pun? I understand, but why are you that mad? Calm down."

So after Posthumous Release, you did put Coma Cinema on hold for a number of years in the 2010s. Elvis Depressedly becomes your focus. Is that because materially it made sense? You were getting an offer to make an Elvis Depressedly record, basically?

Yeah, I mean more people were listening to it and those were the songs at shows where people were singing along. And then we’d pull a Coma Cinema song out and people would be like, “What the fuck is this shit?” So we just stayed with it. Holo Pleasures has that sound where…I love My Bloody Valentine, as I know you do. And I really wanted to make something that was in that lineage of My Bloody Valentine, because they hadn’t made a record in 20 years. I was like, “I’m gonna do something that has that essence with the androgyny and the sensuality of Loveless, and the haze and that kind of melody.”

And then that fucker Kevin Shields puts out another My Bloody Valentine record that year. I was so mad. So actually, maybe if I try to make another shoegaze record, they’ll drop again. But yeah, people just really connected with that stuff and that was the show offers. People were offering us tours, so we took it. I mentioned Mitski earlier, I think we had a really good tour. I think that that was a good lineup, I think it sounded cool together. I toured with LVL Up, who were amazing. The tour with Alex [G] was incredible, a really fun time. But then we would open for bands like The Front Bottoms.

I saw you guys on that tour.

Cool. It was a weird vibe in there. A lot of the people didn’t want us to be there.

I remember you guys rocking out. I was like, “Wow, this sounds so different live.”

Yeah. It’s always hard for me to get on a stage and not want to rock out. I mean, I was three and four and five watching Kurt Cobain on TV. So it's hard for me not to do that when I see a stage. But yeah, it was not a good fit [with The Front Bottoms]. I had a good time with those guys, they were nice guys. But their fans did not like us. And I didn’t like them. Fuck ‘em. They were 12-year-old girls and 25-year-old frat boys. Those were their fans, and I thought they were all a bunch of assholes.

I remember there was one show where these girls were throwing stuff at us and yelling at us, and I remember pointing to them and being like, “Those kids are drinking underage. Get those kids out of here.” Doing shit like that was fun. They had a cool attitude, though, The Front Bottoms. They were cool with us making fun of their fans because they hated their fans as well. They were getting really popular really fast…Sometimes we’d play for like 2,000 people on that tour. And they were shocked, too. They were like, “What the fuck? This is scary.” I think they were struggling. Are they still a band?

Yeah, they’ve put out a lot of records that aren’t very good, pretty much since that tour. And they still play pretty big rooms but I think they might’ve peaked at a certain point.

You only need one. You only need one, big, big record and you can do it forever. I saw Crazy Town one time. I played in the room next to them, a sold-out show, and then I went over to their room and there was like three people there. They played “Butterfly” twice, which I was very happy about because that's kind of a cool song. But it wasn’t sad to see, it was interesting to see. I remember watching it and being like, “This’ll be me someday. I’ll be playing ‘Weird Honey’ for three people while some young band comes over and says, ‘Oh shit, remember this fucking thing?’”

You can’t be afraid of falling off and shit, or you’ll lose your mind. Because you’re going to fall off. Bob Dylan fell off. I like his 80s and 90s records a lot, I like a lot of records made by people who are past their prime. But everyone falls off. Some gracefully, some in completely psychotic ways. And that's just the nature of the game.

Elvis Depressedly was just you at first, but at a certain point the identity of the band became you and Delaney Mills. When did she come into the picture with that band?

Well, we were together for a long time. I think, in a sense, I was trying to infuse every aspect of my life into one thing so I wouldn’t have to take my focus away from anything. It was kind of a doomed relationship because of that. And then she increasingly became pretty deranged, I guess you’d say. It became a very abusive relationship. I felt like my mother with my father. It felt like I was reliving that situation. I felt trapped in it.

There was a lot of anger from her that it was my songs that were being played. There was a lot of shows where she’d try and sabotage the show. And then when I finally got free of that relationship, I was able to process it more and see that I was in some Stockholm Syndrome situation. We haven’t talked in a long time, and I don’t think I’ll ever talk to her again. Especially now, to see the sad alt-right pipeline she’s gone down, is really depressing. That kind of thing is…I don’t understand it and it’s hard for me to speak kindly about those kinds of people.

That was never something you were into, right?

When I was 19 or 20 I was a libertarian, which I think a lot of kids are. Because it’s like, “legalize drugs and don’t go to war,” is what they tell you it’s about. But when you dig a little deeper it’s really about racism, classism, and a love of corporation and oligarchy. I moved away from that. I had a leftist community college teacher who was actually the daughter of one of the former prime ministers of Poland. And she was beautiful.

She used to call me into her office. I’d be hanging out with a bunch of dorky community college guys and she’d be like, “Mathew, come here, I want to talk to you.” And I’d look at the guys and be like, “see you guys later,” and go in the office. And all she would do is berate me about supporting Ron Paul. She’d be like, “you’re an idiot for this, don’t you understand that this is this…” She had a lot of good points and she made me open my mind. And from my early twenties on, I was always someone who is on the left, and I only get further left as I get older.

My stepdad used to say that if you’re young and conservative you have no heart; if you’re old and liberal you have no brain. That's like an old Boomer type joke. But that's not really true. It’s just about wanting people to have fucking dignity and peace in their lives and freedom of expression…In [Delaney’s] case, because I haven’t talked to her in so long it’s hard to say, but I think it’s just narcissism, drug abuse, spiraling. I’m so happy to be free of that situation.

It’s hard to say any of it was good because I do feel kind of preyed upon or whatever. And there were people in my life who kind of used me because of the sort of A&R mindset I had and the sort of putting people on mindset. There were people who tried to be friendly with me and make me feel like we were connected and then I realized later on that they were just manipulating me to get something they thought I could give them. But they would have been much better off manipulating someone with more clout.

I think I have some vulnerabilities I’m still working on about trusting people. Because you don’t want to not trust anyone, but you don’t want to get abused and used up either. You got to find a balance, and I’m still trying to figure out that balance…I have found out who my true homies are and who really stuck by me and those are the most successful people in my life. People like Alex [G] have always been there for me.

You still have a relationship with him?

Oh yeah, yeah.

What does that entail? You guys just talk a lot?

Yeah, just shooting the shit. He reads a lot, we’ll suggest books and stuff. When he comes to town I go and see him. Being a part of his art in any way and being there to see it in the way I got to is truly one of the great blessings of my life. You don’t get to be someone who got to see Prince play, or Neil Young. And to be there for so much of that is incredible. I know he’s one of your favorite artists. He’s one of my favorite artists and would be whether we were friends or not. When I first heard his music I was like, “this is what should be popular.” And now that it’s captured so many people, it feels so good.

I feel like his rise is the ultimate victory against that bullshit, posturing indie-rock that I was talking about. I feel like that's the real nail in the coffin to that stuff and a return to a true honest expression, not just for looks and to be seen and to get your picture with fucking flash photography at the Svedka party. I was right to think that shit was bullshit and I was right to think that this shit is better. And a lot of people agree with me because a lot of people love this music.

How much damage do you think dating your bandmate, as you did with Delaney, did to Elvis Depressedly?

I think for an artist it can be so hard to compartmentalize in a healthy way. And not just romantic relationships but in your friends, too, you need to be able to be a person who’s not expected to be an artist and you need someone who can bring you out of that…cause it’s a stressful thing to be in all the time. I think you got to be able to decompress and come out of that, and it wasn’t possible. And my coping mechanisms have never been healthy. Drugs and alcohol, those are the two worst ones. That didn’t help anything.

I just wanted to turn the noise off while simultaneously feeling the noise. I could have at any point just said “fuck this shit” and disappeared like Jeff Mangum and worked at Walmart. I could’ve done that but I kept going, I kept pushing, and I kept trying to please everyone trying to make this thing mean something. I remember always telling myself that it was gonna stop. “In a couple months, no one will want to book us, no one will want to listen to us, it’ll be over.” And it just never was and it kept going and going and going. I’d do shows and they would sell out. I’d do a record and people would listen to it. Things weren’t really flopping.

So I kept going and on some level you feel lucky. Like, “I’m so lucky that people care,” and you are lucky. But you have to question it and be like, “is this what I want?” And you start to do things for the wrong reasons. You start to make things and think, “Will people like this?” Or you try to make a hit song, and the art suffers, too.

Was there a song you wrote that you hoped would be a hit?

Bunch of ‘em. But now when I look back I’m like, how strange and deluded would I be? This song could never be a hit. It’s not that I think it’s a bad song, some of these songs I think are great. But there’s no world where these songs would be a hit song.

Which ones? I’m curious.

I felt like “Peace on Earth” from Depressedelica. I was like, “it’s a hit song, man. It’s got a hot bassline.” But the lyrics are about angels killing each other and shit like that. “Hold Me Down” off of Who Owns the Graveyard?, to me was a hit song. But on the other hand, [I'm] making snap music cause [I] like that shit. Cause I like the New Boyz. I think “Tie Me Down” is one of the greatest songs ever made. “Kiss Me Thru the Phone” by Soulja Boy and all this shit. But I’m making that so it’s different. It’s not the same as the New Boyz making it, as much as I want it to be.

I’m feeling really good now. I do think I’m more situated in my songwriting than ever before. I started caring about lyrics in a new way, I don’t just toss them off anymore. I started thinking about what I was writing and there’s a lot of joy now that I haven't felt since I just started. When I was like, “I don’t have a drum kit, how do I make a snare? I’ll put some guitar strings in a box and duct tape the box and when I hit it it’ll sound like a snare.” I’m back in that mindset where I’m exploring and having fun.

Like, when Sam [Ray, Teen Suicide] said all those crazy lies about me, it was horrible. And there were some other things that happened, too. Him and his friends swatted me where they got the police called to my house and told them I had a gun, so the police showed up to my house. This happened twice. And they were at parties saying they were hoping I killed myself. Real fucked up type shit. But it was also extremely liberating because I have no fear now.

There was a lot of people walking around on eggshells all throughout that era of my art life, where people who had good intentions in their heart were deathly afraid of saying the wrong thing. Because there were people in the game that wanted to further their own art by making someone else go away. And people were abusing the desire for justice by using certain words and stuff to dominate these social conflicts that had nothing to do with the issues that they were using. I think a lof of people were walking around a little nervous all the time about being taken the wrong way or whatever,

Because I’m on the other side of something like that, I have no fear now, because I know what’s in my heart. So if people want to say something about me that's not true, I don’t fear that anymore because I feel confident enough to say that's not true and if people don’t believe me that's on them. I live my life everyday trying to be honest and real about who I am and what I think, and not having that fear is liberating.

I don’t think anything that I could express about myself is going to hurt somebody else. I don’t think I hold views that would hurt people, and if I were to hurt somebody with something I said, then I would listen to that person and evaluate if that was valid, and then I would change. I don’t go through life feeling like a villain because I’m not. That took a lot of struggling to get to that point. When you’re being gaslit in such a way you start to question yourself. It’s definitely behind me now. I feel free of that burden.

There’s been a lot of times where it seems like you’ve been the victim or have been taken advantage of. Are there times when you’ve been the perpetrator? It’s never as black and white as, “I’m always the victim.” Now that you’re looking back at all these experiences with clear eyes, do you think there were times where you were in the wrong, too?

Yeah. Those times where I’ve hurt people I’ve cared about, I’m close with those people still. Because I have apologized or I’ve understood their perspective, or I healed that relationship. My friend Jones who did the “Weird Honey” bassline. There were times where I was cruel to him. Where I said things that weren’t true like, “Oh, he didn’t really contribute to those songs, fuck him.” Because we had some sort of interpersonal problem. But we dealt with that, we came together, and he was forgiving. I was able to admit that that was wrong, that what I was doing was because I was in pain and I was lashing out.

There’s lots of situations in life like that. I think we have to be open in our heart to forgiving people. And we also have to be worth forgiving when we do something wrong, by being honest. I would forgive almost anyone in my life if they were to be honest. I do think that there’s some conflicts that just never resolve, there’s always going to be negativity. And that's just life, too. Not everyone’s meant to get along. But you’re right, I don’t want to have a fucking excuse for everything.

But the other thing about these situations…we live in a world where everything is so publicized. Even within our small media circles, so many of these issues have no place in the greater visibility of society. It’s stuff you work out in your own community. And I think in my era, there was this huge need to do everything in full view of everyone. Everything had to have an audience. Everything was content.

Everyone is guilty, in my mind, of really enjoying when someone gets canceled. You’re like, “Oh shit.” You read the thing and you talk with your friends and you get in your group chats and you’re like, “Look what happened.” Everyone’s guilty of that. But that's unhealthy. These are real people who are suffering in full view of the public.

You said that you were beginning to feel like you were compromising and putting too much effort into writing “hits.” But it seemed like you were aware of that as it was happening. On Depressedelica, you had the song “Peace on Earth” that you thought could be a hit, but you also had “Let’s Break Up the Band,” which is this peaceful acceptance of a band’s conclusion. On Who Owns the Graveyard?, you had that song you hoped would take on a life of its own, but you also had “Lay It In” where you sing, “I let my art be my job/let the job steal my soul.” Were you kind of realizing what was happening but letting it happen anyways?

Oh, absolutely. I think what a lot of people know and realize, but they don’t want to admit it – and it’s hard for me to admit it – but we’re not defined people. Things change all the time, and I’m even more susceptible to that because my emotions can make me think insane things. I’ve been so crazy at some points that I thought there was fucking cameras in my walls.

Also, being in those worlds of the music industry and stuff, when you’re in a manic mood and people tell you, “Oh yeah, you could really blow up. You could be this. You go open for this band and then this thing will happen, it’s a sure bet.” And you start to believe it and you start to think, “Oh wow, I could be famous,” and then you start to entertain that idea. And that overtakes the original desire and passion of just creating art. And you stop thinking about creating art and you start thinking about what you’re going to say to Kurt Loder. You start thinking about shit like that instead of shit that fucking matters, and then you get off track. You get distracted. And then people take advantage of you in the business.

There’s shady stuff. One of the members of Grizzly Bear wrote me an email when I put out the video for “Flower Pills” and he was like, “Hey, I really like your video for ‘Flower Pills.’” And I was like, “Oh, cool, the Grizzly Bear likes my video.” And I kept reading and he was like, “I’m starting this label called Terrible Records.” And I’m thinking, “Oh, he’s gonna want to sign me. This is fucking awesome.” And then he gets to the end and he says, “Can you take your music out of the video and put this band’s music in?” And I was like, “What?”

So immediately my brain switches into “fuck you" mode, so I’m like, “Fuck you asshole, you piece of shit. Mother fucking born rich bastard. I’ll fuckin kick the shit out of you.” That's the kind of thing, though, that people will ask you. It’s absurd, the things that people will want to do. I fell for it many times. I’m not sitting here knowing what’s happening to me, I’m just like, “Oh cool, these people want to help me out. These people like my shit.” And you go along with it.